UF Health researchers study association between type 2 diabetes and fatty liver disease

Too often, the wisps of smoke go unnoticed long before the raging conflagration erupts.

The story of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, or NAFLD, is often filled with missed opportunities to catch the disease before it grows into life-threatening cirrhosis, especially for patients with Type 2 diabetes, said University of Florida Health endocrinologist Kenneth Cusi.

“You can’t diagnose a disease if you aren’t thinking about it,” said Cusi, M.D., a professor and chief of the UF College of Medicine’s division of endocrinology, diabetes and metabolism.

Too few physician and patients, he said, have NAFLD on their radar.

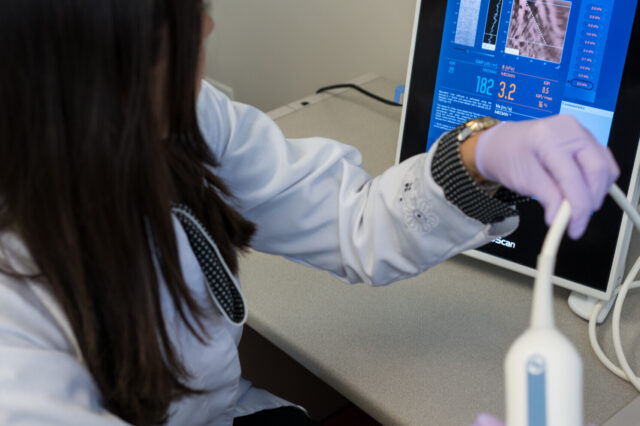

Cusi is leading a recently launched UF Health study that could heighten awareness of fatty liver disease among physicians and those patients who are often the most susceptible — those with Type 2 diabetes. During the next year, Cusi and his collaborators will test 1,000 people with Type 2 diabetes for NAFLD, liver inflammation, scarring and cirrhosis at UF Health clinics. They are using a specialized ultrasound called FibroScan, manufactured by a French company, that can detect the condition more reliably than traditional methods, Cusi said.

Early detection opens the door for interventions such as lifestyle changes, weight loss and medications that can stem or reverse the progression of the disease. For example, a 7 percent reduction in weight can significantly lower liver fat content and inflammation in most patients, Cusi said.

“This is a big public health issue,” he said. “NAFLD is a major epidemic. And the saddest thing is that it’s preventable. If I would have gotten to that person with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease 10 years earlier and treated them, they might not have cirrhosis today. Our mission is to increase awareness among health care providers to start thinking about this, which will lead to earlier diagnoses.”

NAFLD, which swells the liver with fat, is most often, though not always, tied to obesity. Scientists believe a metabolic breakdown in the body, such as that seen in Type 2 diabetes, results in fatty acids being released into the blood, ultimately accumulating in a ready receptacle — the liver.

While some non-U.S. studies have shown a correlation between NAFLD and Type 2 diabetes, the American Diabetes Association has been reluctant to recommend Type 2 patients be tested given the uncertainties about the magnitude of the problem, the challenge of diagnosing NAFLD, and a paucity of treatment options, among other issues, said Cusi.

“The association is accepted, but no prospective study as we plan to do is available to bring this to the attention of physicians as a real, everyday problem affecting millions of people,” Cusi said.

He noted researchers are working to fill in those knowledge gaps. For instance, recent studies by his group indicate that the generic diabetes medication pioglitazone, as well as weight loss, reverses fatty liver in many patients. Several new medications also are undergoing clinical trials.

When too much fat accumulates, Cusi said, liver tissue can send out an SOS signal in the form of inflammation, which can ultimately lead to cirrhosis and liver failure. That more progressive form of the disease is called nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, or NASH.

By 2020, NASH is expected to surpass hepatitis C as the leading cause of liver transplantation.

Many aspects of NAFLD and NASH remain puzzling. For example, not everyone with NAFLD will develop inflammation or cirrhosis. Also, why some patients with Type 2 diabetes develop a fatty liver, while others do not, even when obese, is unknown.

Research indicates 10 percent of children and 20 percent of adults have NAFLD. And Cusi noted that Type 2 diabetics appear to be especially prone, with preliminary research suggesting up to two-thirds suffer from a fatty liver.

Scientists believe up to 5 percent of those Type 2 diabetes have cirrhosis.

“We are potentially incubating several million people on the path to cirrhosis,” said Cusi. “But I think we might be able to catch them before they get there if we get the word out.”

Many aspects of NAFLD and NASH remain puzzling. For example, not everyone with NAFLD will develop inflammation or cirrhosis. Also, why some patients with Type 2 diabetes develop a fatty liver, while others do not, even when obese, is unknown.

Recognition of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease has steadily grown in the last decade or so. Cusi noted that around 2006 just 100 research papers on the subject were published annually. Today, that number is closer to 4,000.

Still, Cusi said, inertia remains and many patients are nonetheless unaware of the breadth of the health threat. “We are still in the infancy of showing that this is a common problem,” he said.

One particular frustration, Cusi said, is that many physicians don’t fully recognize that fatty liver can be stemmed or reversed with weight loss or by some medications.

NAFLD is a complex disease that can ultimately impact several of the body’s systems. In a recent paper published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, Cusi and his co-authors, Norbert Stefan, M.D., and Hans-Ulrich Häring, M.D., both of the University of Tübingen in Germany, called for a multidisciplinary approach to NAFLD to personalize risk prognosis and treatment.

“Endocrinologists, hepatologists, cardiologists and primary care physicians need to work together to turn things around,” Cusi said.

Cusi said he far too often sees patients with cirrhosis who many years before had elevated liver enzymes in routine bloodwork — initial signs of a fatty liver — that were dismissed by a physician.

“I feel strongly that we are wasting time and we have a lot of people who are missing an opportunity to do something about fatty liver,” Cusi said. “We need a major shift in how we think about the disease.”

Collaborating with Cusi on the study are Fernando Bril, M.B.B.S. (M.D.), Romina Lomonaco, M.D., and Diana Barb, M.D., all assistant professors in the UF College of Medicine’s division of endocrinology, diabetes and metabolism.

About the author