New gene therapy for inherited eye disorders found effective in animal model

A new gene therapy developed by University of Florida Health researchers stops vision loss and improves sight in dogs — a key step toward testing the treatment in people affected by a group of genetic eye disorders.

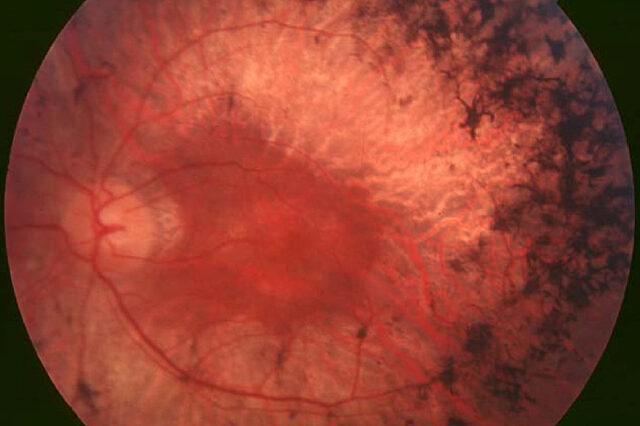

The therapy uses a small, harmless virus to deliver genetic material that blocks and reverses the effects of retinitis pigmentosa, a group of inherited diseases that kills light-sensitive cells in the retina. The gene delivery vehicle, known as an adeno-associated virus, or AAV, vector, is unique for its sight-saving double punch: It silences the mutant rhodopsin gene that causes retinal degeneration while also delivering a normal, replacement copy of the gene. The AAV therapy saved photoreceptor cells and prevented vision loss among the dogs in the study. The findings are published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

It’s the first time that a gene therapy for retinitis pigmentosa has been tested in dogs, said Alfred Lewin, Ph.D., a professor in the UF College of Medicine’s department of molecular genetics and microbiology and a member of the UF Genetics Institute. The virus has already been shown to be safe in humans and was successfully tested several years ago in mice. While much additional research remains before the treatment can be tested or used in people, Lewin is encouraged because dogs and humans both have retinas rich in photoreceptors known as cone cells.

“We were able to save cone vision in the dogs. If we can do that in people, it will save the central vision that allows them to recognize faces, read and watch television,” Lewin said.

UF Health researchers constructed the AAV virus and its genetic payload and tested it in tissue. At the University of Pennsylvania, 10 beagles with naturally occurring retinitis pigmentosa were treated with eye injections by William A. Beltran, Ph.D., D.V.M. and his team. In nine weeks, the AAV therapy “considerably reduced” the level of mutant ribonucleic acid compared with untreated areas of the eye, the researchers found. After more than eight months, the AAV injection had successfully and completely protected rod cells, the other type of photoreceptor cell in the retina, they noted.

“It’s a one treatment fits all,” said Beltran, a professor of ophthalmology at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine and co-lead author of the study. “The treatment targets a region of the rhodopsin gene that is homologous in humans and dogs and is separate from where the mutations are located. That gives us great hope about making this a translational treatment.”

Lewin said he is encouraged by the potential to use the AAV therapy more widely. The researchers set out to develop a genetic “platform” technology that could work on other, similar genetic mutations that cause blindness. Because of the way the AAV therapy works, Lewin said he is hopeful that it could possibly be used against other diseases, like those that cause kidney and liver cysts and also arise from a single copy of a mutant gene.

Finding a gene therapy to address retinitis pigmentosa was particularly challenging because it requires the mutated gene to be silenced rather than simply delivering a functional replacement gene, Lewin said. He credited Michael Massengill, a student in the UF M.D-Ph.D. program, for doing significant work constructing and testing the virus. Massengill received his Ph.D. this month and just resumed medical school at UF.

Next, the researchers will conduct long-term studies in dogs to develop the ideal therapeutic dose. After that, it would be tested for safety in other animal models before possibly moving into a safety study in humans, Lewin said. Samuel Jacobson, M.D., Ph.D., a physician collaborator at the University of Pennsylvania is working to identify the patients who would be eligible. Any potential unanticipated effects of the therapy are now being studied in human cells.

“We’ve known for decades that this specific molecule causes a specific form of retinitis pigmentosa, but developing a treatment has not been straightforward,” said Artur V. Cideciyan, Ph.D., research professor of ophthalmology at Penn Medicine and co-lead author. “Now, with these elegant results based on years of study in dogs we can start working toward treating these mutations and prevent deterioration of photoreceptor cells in humans.”

The new findings are the latest success for UF Health scientists studying gene therapy for vision disorders. A decades-long effort by ophthalmology researcher William Hauswirth, Ph.D., to bring sight to patients who have another genetic form of vision loss was approved by federal officials in late December.

Funding for the current research was provided by the National Eye Institute, Research to Prevent Blindness and The Shaler Richardson Professorship Endowment.

About the author