UF researchers identify drug therapy that could decrease the rewarding effect of methamphetamine

University of Florida neuroscientists have identified a novel way to preventively decrease the reward effects of methamphetamine on the brain using on-the-market medicines, a finding that holds the potential to break the cycle of addiction for methamphetamine users.

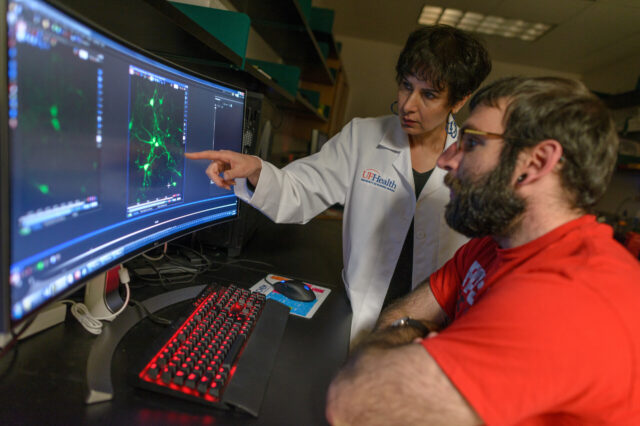

Currently, there are no federally approved therapeutic medicines specifically targeted to treat meth addiction. But in the journal Nature Communications published today, a multi-university team led by UF’s Habibeh Khoshbouei, Ph.D., Pharm.D., demonstrates in a rodent model how preventive use of medications known as sigma-1 receptor agonists — a group including the antidepressant Prozac — decreases the euphoria that normally results from methamphetamine intake.

The researchers found that in mice, a low dose of a sigma-1 receptor agonist thwarts the expected increase in firing activity of dopamine neurons in the brain that goes hand-in-hand with meth use. Dopamine is a chemical messenger released during pleasurable activities such as eating and sex.

“With methamphetamine, the amount of dopamine released is extremely high, so high that people cannot have a semi-normal life,” said Khoshbouei, an associate professor of neuroscience and psychiatry at UF’s College of Medicine, part of UF Health, and a member of the Evelyn F. and William L. McKnight Brain Institute of the University of Florida. “The drug-seeking behavior is so intense that having a normal and productive life becomes all but impossible.”

Khoshbouei described the new findings as a significant advancement toward treating meth addiction. “Our data show that there are drugs already approved for other conditions by the Food and Drug Administration that can help methamphetamine addiction,” she said.

Methamphetamine, a psychostimulant, greatly interferes with the normal transmission of dopamine in the brain. Previous findings by Khoshbouei’s lab show that a meth-induced increase in dopamine lasts for hours, compared with a much shorter time for cocaine. The new study builds upon her lab’s research showing how meth extensively releases dopamine in the brain via a carrier called dopamine transporter in what is called “reverse transport” of dopamine.

Meth also interacts with a signaling modulator in the brain called the sigma-1 receptor, which the researchers identified as a potential molecular target to treat meth addiction.

Using electrophysiology, or measurements of electrical activity generated by neurons, the study found that use of certain medications has the potential to prevent stimulation of dopamine neurons that normally follows meth use. Sigma-1 receptor agonists include some commonly prescribed antidepressants, such as fluvoxamine, and antihistamines, such as dextromethorphan, that can “turn on” the sigma-1 receptor.

Importantly, the study found that sigma-1 receptor agonists, in the absence of methamphetamine, do not provoke the reverse transport of dopamine through its carrier.

The results of the study support the idea that in humans, a sigma-1 receptor agonist such as fluvoxamine or sertraline could potentially thwart the efficacy of meth. The next step would be future clinical trials in humans.

“We were stunned by the finding,” Khoshbouei said. “When you pre-treat the dopaminergic neuron with a sigma-1 receptor agonist, you decrease the methamphetamine-induced increase in intracellular calcium and dopamine release. What this means is that if an animal or human is exposed to this compound, methamphetamine is less effective.”

Khoshbouei draws a parallel to the use of naloxone to block the effect of opioids. One contrast is that the sigma-1 receptor agonist for meth treatment would only be effective when taken prior to meth intake — not to reverse effects afterward. The therapy thus would be suited for people motivated to recover from the addiction.

“Methamphetamine is such a menace because the amount of dopamine released following meth abuse is so huge that after long-term abuse these people experience psychosis,” Khoshbouei said.

If that effect were blocked, she said, “It could really help people to beat their addiction.”

About the author