The Quality and Safety Journey at UF Health Jacksonville

In October of this year, we received great news from Vizient, which benchmarks various measures of patient care quality and safety for 114 academic health center hospitals: UF Health Jacksonville had zoomed up 33 spots in the rankings — from 77 to 44. Moreover, UF Health Jacksonville was awarded the inaugural Vizient Innovation Excellence Award last year, in recognition of its innovative technology to enhance patient care.

The goal for both UF Health Shands and UF Health Jacksonville is to be in the top 10, so there’s much work to be done. Yet, the dramatic improvement at UF Health Jacksonville was deeply satisfying for faculty, staff and leadership, as it represented a successful reversal of the Vizient report in October 2014, when we learned that, after steadily rising in the annual quality rankings, UF Health Jacksonville had fallen to the lowest quartile.

As is clear from the 2017 Vizient data, UF Health Jacksonville is now moving solidly in the right direction with regard to quality and safety. Moreover, recent results suggest that these improvements are continuing. This issue of On the Same Page tells this remarkable story.

Historical Context

Let’s go back to the fall of 2014. While the initial instinct among many clinical organizations when confronted with data they don’t like is to mount a spirited defense against those data, CEO Russ Armistead and the Jacksonville leadership team were clearly committed to working toward a new paradigm that would turn things around.

As a core principle, we understood that patient care quality does indeed need to be Job 1. If quality is recognized as the fundamental operating principle driving an academic health center, then not only is patient care enhanced but the AHC’s education and research missions follow naturally; if not, then not only is patient care compromised but the academic missions also are difficult, if not impossible, to achieve.

We conducted a systemwide autopsy to determine what happened and why. Importantly, it was an autopsy without blame, in which root causes were nonjudgmentally identified. From this process, a path forward was defined. A major decision was to appoint a physician as chief quality officer, someone inside the organization who is universally respected for clinical acumen and judgment, who has displayed an ongoing commitment to quality, and who has the administrative skills to pull off the turnaround. Luckily, it turned out that this walks-on-water person was indeed among us: Kelly Gray-Eurom, M.D., a professor of emergency medicine, was appointed chief quality officer at UF Health Jacksonville and assistant dean of quality and safety at the UF College of Medicine-Jacksonville, since the patient experience traverses outpatient and inpatient settings. Both of these titles were new positions that did not previously exist in the organization.

We conducted a systemwide autopsy to determine what happened and why. Importantly, it was an autopsy without blame, in which root causes were nonjudgmentally identified. From this process, a path forward was defined. A major decision was to appoint a physician as chief quality officer, someone inside the organization who is universally respected for clinical acumen and judgment, who has displayed an ongoing commitment to quality, and who has the administrative skills to pull off the turnaround. Luckily, it turned out that this walks-on-water person was indeed among us: Kelly Gray-Eurom, M.D., a professor of emergency medicine, was appointed chief quality officer at UF Health Jacksonville and assistant dean of quality and safety at the UF College of Medicine-Jacksonville, since the patient experience traverses outpatient and inpatient settings. Both of these titles were new positions that did not previously exist in the organization.

Once this was done, findings and recommendations from the “autopsy” were provided to Dr. Gray-Eurom, and she was also given the flexibility and authority to supplement or modify these with her own assessments and to develop her own initiatives. In early 2015, Dr. Gray-Eurom presented her plan to the UF Health Jacksonville leadership and hospital board, which was enthusiastically supportive.

Contributors to Success

As a preface to the factors contributing to UF Health Jacksonville’s success in improving patient care quality and safety, Dr. Gray-Eurom first gives credit to senior leadership at UF Health Jacksonville: “Change in Jacksonville has been encouraged from the very top. Mr. Armistead, Dr. Vukich [chief medical officer], and now Dr. Haley [dean of the College of Medicine-Jacksonville] have clearly made quality a priority. It is a key item on hospital and practice plan agendas. Senior leadership actively participates in patient safety rounds on the units. And quality is always mentioned in the biweekly CEO video ‘A Few Minutes with Russ,’ which has now become ‘A Few Minutes with Us’ with the addition of Dean Haley. Staff and employees know quality is important because “Mr. Russ says so.”

According to Dr. Gray-Eurom, when she started in her new role it quickly became apparent that many quality projects were in process, but the organization had not fully prioritized such projects based on patient care impact, nor had it clearly defined a methodology for implementation. Those missing elements created a “project-de-jours” environment. Each project had value, but when everything has equal value, it is hard to move forward. Dr. Gray-Eurom therefore created a new structure. With the help of Susan Hendrickson, division director of quality management, teams were reorganized and new work designs were put into place. Focused on the patient, the overarching goals were to eliminate silos, prioritize work projects and keep the bedside providers in mind with each and every change. As a result, work projects were aligned with patient care goals and were prioritized, so that limited resources could be deployed more effectively.

A unique and deliberate structure in Jacksonville that has allowed successful collaboration and economies of scale is the configuration of the Jacksonville Quality Division. This quality division now integrates a number of activities that were in disparate parts of the organization: patient safety, infection prevention & control, risk management, accreditation, quality abstraction and performance improvement. As Dr. Gray-Eurom puts it: “This coherent structure decreases overlapping work, eliminates silos and creates an environment that supports communication across all employees who work on quality, prevention and risk management issues.”

Dr. Gray-Eurom also found that “many physician faculty in Jacksonville were unclear about the rationale behind particular patient care goals. Many did not trust the outdated data that had been provided. Many wanted to help but were unsure where to start. Providing real-time data in a meaningful format was critical for physician engagement and trust. Departmental dashboards with provider-specific data were created and providers had the opportunity for meaningful two-way discussions. These data were used to improve patient care and patient care processes, not to fault-find. I hold monthly meetings with all of the chairs to provide data and make sure they understand what the objectives are and to get their buy-in. Physicians from every department are now actively providing solutions and interacting with quality in a way they never experienced before. Provider-developed initiatives driven by literature-based best practices are being combined with system changes through protocols, Epic orders and housewide education.”

Dr. Gray-Eurom also refocused the work of various performance improvement committees, or PICs — moving them from a forum for communication to a platform for action. The goal was to “lower the barriers that interfered with patient care across the continuum.” Instead of working with a dizzying array of policies that were embedded in the various PICs — nursing, medical, surgical, ambulatory — these policies are now the same. Instead of the PICs serving as an informational forum for various clinical arenas in isolation, they are now coordinated as an impetus for constructive change across the system.

Case Studies

Catheter-associated urinary tract infection and the safety domain

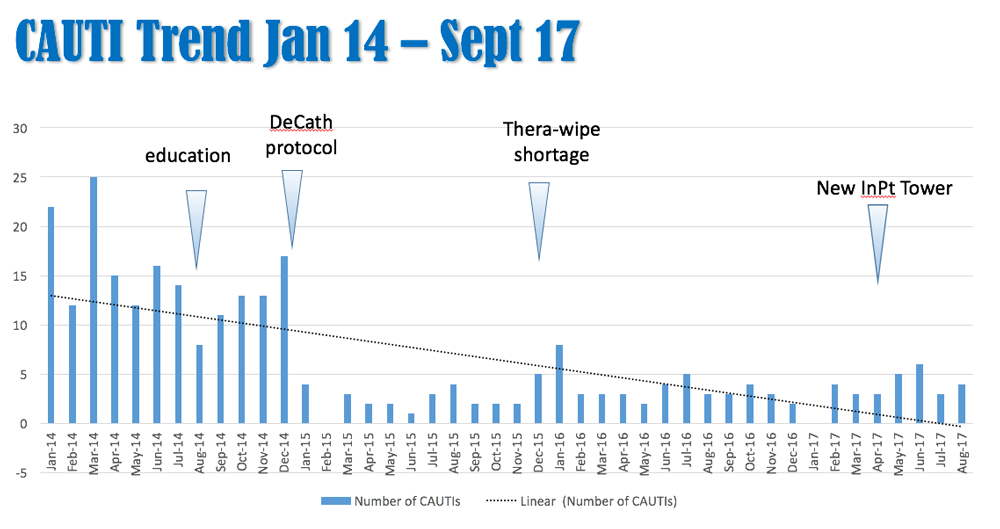

A good example of collaborative systems that have been successful at UF Health Jacksonville is the story of how catheter-associated urinary tract infections, or CAUTIs, have been reduced dramatically. Previously, education had been provided on indications and care management for urinary catheters. Education alone, however, was not making a sustained impact. Therefore, Dr. Gray-Eurom enlisted a team of nurses and physicians to work together with information technology to address the issue.

One important initiative has been a medical-staff approved, nurse-driven protocol for removing Foley catheters without the requirement of a physician order (“Decath Protocol”). Also, there are now clearly stated indications for which patients need indwelling Foley catheters and which do not. Examples: a physician order for “strict I&Os” (intravenous inputs and urinary outputs) no longer requires an indwelling catheter; obstetrical patients with epidurals don’t require an indwelling catheter; and on a variety of medical and surgical services, a bladder ultrasound scanner that a nurse can use to read out urinary volume is used in protocols to confirm proper bladder emptying, rather than relying on an indwelling catheter. In addition, staff from infection prevention and control provide immediate unit feedback, which allows the patient care teams to monitor patient progress and to find solutions rapidly when needed. Bedside staff have interactive avenues for communication about equipment issues. Those communications are used to change items that are not working and add equipment where needed. As seen in the graph below, combining education with a systems change that is supported by meaningful feedback loops has shown sustained results with respect to catheter-associated urinary tract infections.

The CAUTI rate is just one of the elements used to assess safety by Vizient. Dr. Gray-Eurom states that “literally hundreds of people are responsible for the great strides in safety at UF Health Jacksonville. Directors, managers and clinical quality nurse leaders help educate and promote best practices. House staff are key in protocol development and care delivery. The Jacksonville faculty have been incredibly open and supportive in creating and adopting evidence-based protocols to improve quality on campus. Setting the overarching goals, combining education with systems changes, engaging providers at every level and leveraging the technologies in the electronic health record have set a very positive course for the campus.”

These efforts have yielded tremendous improvements in safety metrics. In the last three years, UF Health Jacksonville has shown the following decreases in clinical events that comprise the Vizient safety domain:

- 74% decrease in urinary tract infections

- 57% decrease in pressure ulcers

- 66% decrease in central-line infections

- 70% decrease in surgical infections

- 78% decrease in respiratory failure

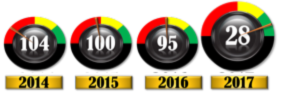

Collectively, these results have led to an extraordinary improvement in the overall 2017 UF Health Jacksonville safety ratings, jumping from a ranking of 95th to 28th in safety / hospital acquired conditions among the academic health center hospitals tracked by Vizient.

UF Health Jacksonville Vizient Safety Domain

UF Health Jacksonville Vizient Safety Domain

Central-line-associated bloodstream infections

Reducing infections related to central lines was a top priority project for the organization. A central line is a specialized intravenous catheter that allows for large volumes of medications to infuse at a rapid rate. They also have several access ports to allowing multiple medications to infuse at the same time. Central lines are therefore an important part of care in stabilizing critically ill patients. Reducing the number of days that the central line remains in place, however, is an important part of reducing the risk of central-line-associated bloodstream infection, or CLABSI. Central lines were sometimes remaining in place for too long in Jacksonville (and in many other hospitals) because the nurses and doctors didn’t want to risk losing needed IV access by removing the central line “too early.” An alternative needed to be found.

In collaboration with physicians, nursing, quality and equipment management, Cynthia Gerdik, R.N., D.N.P., proposed initiating an ultrasound-guided midline insertion team. A “midline” IV catheter is a very stable, three-port access peripheral IV that is placed under ultrasound guidance. Midlines can remain in place for up to 30 days and provide an excellent alternative to a central line when the patient has stabilized. Emergency medical technicians in the ED were already trained in ultrasound-guided peripheral IV insertion. Dr. Petra Duran, the head of ED ultrasound services, created a training and competency program for the EMTs. Once deemed competent, the EMTs could place ultrasound-guided midlines. Any patient who required a central line for critical care treatment in the emergency room also had a midline placed by the EMTs. The midline allowed inpatient critical care teams to remove the central line as soon as the patient stabilized in the intensive care unit.

Prior to the midline insertion team, central lines days averaged between 2,505 and 2,755 per month, with nine to 15 infections each month. With the addition of midline access, central line days decreased to approximately 1,600 per month and infections decrease to 0 to four per month. This also proved to be a very cost-effective outcome in terms of a reduction in costs associated with IV personnel, antibiotic usage and length of stay. This program has been expanded to other areas of the hospital where long-term infusions are done.

Sepsis

Sepsis is an overwhelming infection that can causes organ compromise, organ failure and death. It is a leading cause of inpatient mortality across the country. At UF Health Jacksonville, it was the third-leading cause of inpatient mortality. Dr. Gray-Eurom brought together a sepsis team led by Dr. Faheem Guirgis, an assistant professor of emergency medicine, Dr. Lisa Jones, an associate professor and chief of pulmonary critical care, and Rhemar Esma, lead quality analyst. The sepsis team implemented an evidence-based sepsis bundle of care and an early recognition system — the Azreal early sepsis notification program — that is triggered directly from the electronic medical record. Thus, a hospitalwide change was implemented in how sepsis is recognized and treated.

The Azreal program electronically scans the patient record every hour. If the patient’s condition, vital signs and lab values meet certain thresholds, an alert is automatically sent to the patient’s care team. That team responds at the patient bedside and care is therefore initiated at the earliest possible signs of sepsis. The sepsis care bundle was organized into an easy-to-use Epic order set that automatically brings the needed resources and the correct treatment to the patient.

This early recognition system and use of the sepsis bundle of care has resulted in a dramatic improvement in sepsis mortality at UF Health Jacksonville. The observed:expected sepsis mortality index is used by Vizient to assess sepsis mortality across hospitals. An index of 1.00 means that, given the distribution of patient diagnoses and complexity in a hospital, the mortality rate in that hospital is what would be expected. An index higher than one means that mortality is worse than expected and an index below one means that mortality is better than expected. In 2017, the observed:expected sepsis mortality index was 0.86. This compares with 1.23 in 2014, prior to initiation of the interventions described above. Moreover, reducing sepsis mortality has been an important factor in reducing the overall inpatient mortality index at UF Health Jacksonville, which declined from 1.05 in 2014 to 0.73 in 2017.

UF Health is dedicated to patient quality and safety as Job 1. The extraordinary improvement in quality and safety at UF Health Jacksonville, in the face of a patient population with limited resources and a facility that needs significant upgrading and modernization, demonstrates that, at the end of the day, it is our people — leadership, faculty and staff — who make the difference. Embracing discouraging data as facts that need to be addressed rather than explained away, committing to fundamental change, and working hard across all layers of the organization to implement change successfully is an inspiring commentary on the dedication and talent of those who work at UF Health Jacksonville.

The Power of Together,

David S. Guzick, M.D., Ph.D. Senior Vice President for Health Affairs, UF President, UF Health

About the author