Putting Practice into Action

For 18 years, Sandra “Sandy” Demasters-Reynolds, M.S.N, R.N., CCTC, has served as the living donor program manager at the UF Health Shands Transplant Center. But Sandy never really thought of becoming a living organ donor herself until organ failure affected a loved one of her own.

Sandy’s brother-in-law, Dave, was diagnosed with polycystic kidney disease, an inherited disorder that causes cysts to develop within the kidneys and disrupt kidney function. The 66-year-old knew his mother had kidney failure and was on dialysis, but he did not know what caused her kidneys to fail. Dave was diagnosed after his daughter was diagnosed with the disease in her early teens.

Dave, who lives on a farm in Tennessee, always kept himself busy. Whether it was tending to their horses or working multiple trades, he monitored himself routinely and continued to live an active lifestyle.

In the summer of 2018, Dave started to feel the effects of his disease. As his condition worsened, he had to initiate renal replacement therapy in the form of home kidney hemodialysis with the help of his wife, Billie, also a nurse.

Several days each week, Dave spent two to four hours on dialysis, with an additional hour and a half to set up and prime equipment. “They were doing home dialysis and Billie sent a picture of him sitting on the dialysis machine smiling,” Sandy recalled. “I‘m like, ‘That’s not Dave, he’s much more active than that. He deserves a chance to get off of dialysis through transplant.’”

Sandy, who also previously interacted with many liver, kidney and kidney-pancreas transplant patients in the UF Health surgical intensive care unit, explained that patients who need dialysis often have to visit dialysis centers three days a week for hemodialysis. They cannot perform home hemodialysis for a variety of reasons, such as not having a support person to assist, having a difficult time performing dialysis at home and not living in an environment suitable for the dialysis to occur.

Dave was evaluated and placed on the kidney transplant list. He had four potential donors apply to donate a kidney but each living donor fell through, primarily because of preexisting conditions.

Sandy knew she couldn’t sit idle while Dave’s condition continued to deteriorate. She knew the average life of a patient on dialysis is five years. She wanted Dave and Billie to be able to enjoy the retirement they had worked so hard to prepare.

So, Sandy started the process to become a living kidney donor. She completed an online application, submitted her medical history and physical labs and waited to be contacted. Since her brother-in-law lived out of state and was receiving care elsewhere, Sandy intended to travel to his home for care — if she was approved as a donor.

After passing the initial application and medical history component, Sandy traveled for a two-day evaluation that included ensuring her kidneys were functioning properly and that she could function without the need for both kidneys.

Doctors approved Sandy for the procedure, but there was a caveat: She was not the correct blood match for her brother and, therefore, could not donate her organ to him.

Instead of being Dave’s living donor, Sandy and Dave were registered on the paired kidney donation list. Part of the living kidney donor program, paired kidney donations are situations when a recipient and donor who do not match blood types find another recipient and donor in the same situation, and swap organs.

Sandy explained that there are many misconceptions surrounding living donor programs, one myth being that a person cannot be a living donor if they are not blood-related. Other misconceptions include believing that their religion won’t support organ donation when, in fact, all major religions in the U.S. support living and deceased organ donation — even those that are against blood transfusions. Other common misconceptions include that a person cannot live with one kidney and that they’ll need another later in life, as well as the belief that out-of-pocket costs for the donor will be too high.

In general, living donors need to be between the ages of 18 and 70. Donors must be willing to donate, have a blood type that is compatible with the recipients, or agree to paired donation, as well as not have diabetes, or high blood pressure that requires being on multiple blood pressure medications.

“I knew paired donation was our only option. I knew with the paired donation, we’re not only helping my brother-in-law and the other paired recipient get a kidney, but two others can receive a deceased donor kidney,” Sandy said. “Four people in need of a kidney transplant were helped. Two receiving a living donor kidney, which removed them from the deceased donor list and allowed two deceased donor kidneys to go to other candidates in need of a transplant.”

On Dec. 2, 2019, Sandy received a call that there was a potential pair and, if everything worked out, the surgery would take place on Jan. 2, 2020 — one day before her 60th birthday.

Prior to the procedure, Sandy reached out to longtime colleague Kenneth Andreoni, M.D., a transplant surgeon and the chief of transplantation surgery at the UF Health Shands Transplant Center, to connect with her surgeon.

The transplant program at UF Health has been part of three-way and two-way swaps. This involves staff at both transplant centers coordinating operating room times for donors, kidney travel from one center to the other and the recipient surgery to transplant the donated kidney.

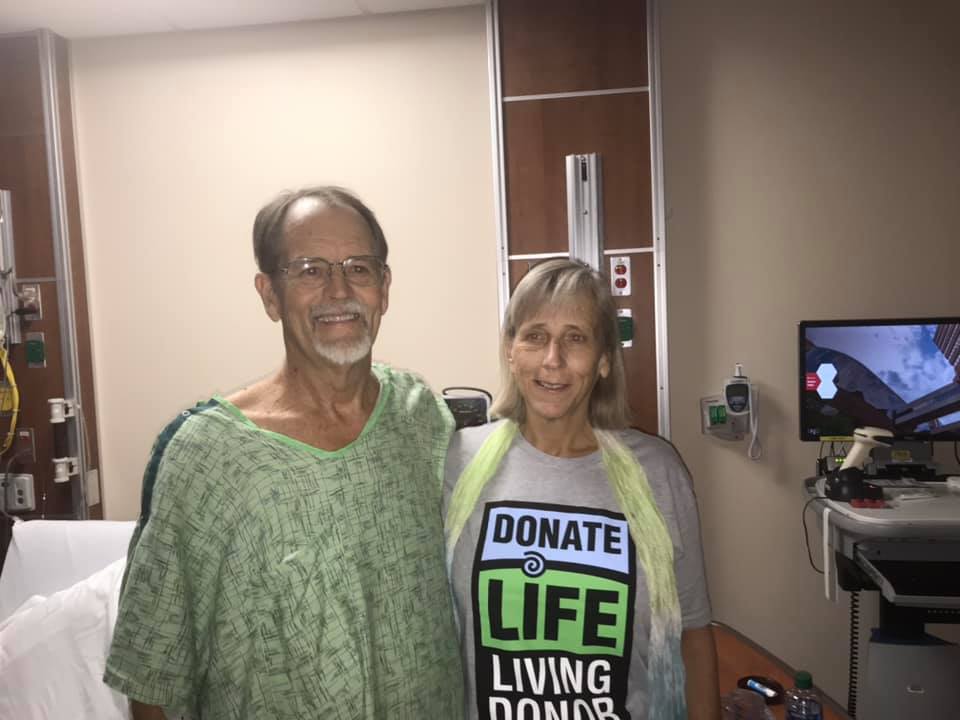

After the surgery, Sandy spent two days in the hospital and four to five weeks recovering before returning to work. She will have routine six-month, one-year and two-year follow up appointments in Gainesville. Dave is recovering well and adjusting to life as a transplant recipient.

This experience has expanded Sandy’s role at the UF Health Shands Transplant Center far beyond a program manager. She’s not only a donor herself, she’s become an advocate for other living donors and a community speaker about living donation.

“I feel I have a new purpose in life, to share about living donation and paired donation. I want to share my story to encourage other potential living donors,” she said.

Sandy makes it her mission to visit all of the living donors from UF Health to answer any questions they might have about the recovery and to say thank you.

“I feel it is important to visit our UF Health living donors,” Sandy said. “I am another face to say thank you because I feel they cannot hear it enough. A living donor has agreed to have a surgery they do not need in order to help another person. What a selfless gift! And the donor may not realize they have helped more than one person.”

About the author