Preventing Sepsis & Treating Deadly Infections: Adam Nickels’ Story

Adam Nickels felt fine, until he didn’t.

Nickels was working toward a doctorate in aerospace engineering at the University of Florida late last year. He enjoyed being active; lifting weights, hiking, biking and riding his motorcycle. Christmas was just around the corner, and Nickels was looking forward to the holiday break, blissfully unaware that he soon would be fighting for his life.

On a Monday morning, Nickels went to work feeling normal. Around midday, he began to feel like he had the flu. Shivering with fever, Nickels went home and decided not to go to into work the next day.

Nickels knew he was sick but didn’t have any inkling how bad he was until a coworker’s wife and UF medical student, Cindy Medina, stopped by.

“She came over and gave me some soup and noticed spots on my hands that I hadn’t seen,” Nickels said. “She told me that I needed to go to the hospital because illnesses that had spots were not good.”

Though Nickels had never wanted to be an interesting medical case, his mysterious sickness rapidly turned him into one. He went to the UF Health Shands Emergency Center – Springhill, where doctors quickly decided to transfer him to UF Health Shands Hospital.

Nickels began to realize that things were seriously wrong with his health.

“I went to use the restroom and by the time I got back to my room, things fell apart,” Nickels said. “I got viciously sick. I was throwing up and my head was in the most pain it’s ever been in.”

During the ride to the hospital, Nickels’ pain was so severe that friends had to answer medical questions for him. Once there, doctors performed a variety of tests that quickly confirmed their suspicions.

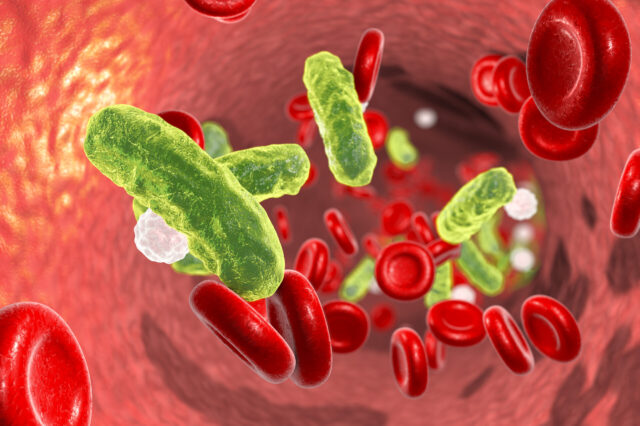

Nickels had meningococcemia, a blood infection caused by a bacterium called Neisseria meningitidis, which can also cause meningitis B. The rare infection can cause a person to feel sick in the morning and die by the afternoon. As this bacterium is known to thrive on college campuses, where students live and interact in close quarters, most university students are aware of the risk and are vaccinated for N. meningitidis before their first year on campus. This vaccine, however, does not cover all strains of the infectious agent. Nickels, who thinks he had the vaccine, doesn’t know how he could have contracted the illness.

“There was nothing out of the ordinary that I did the couple of days before that,” Nickels said. “I have no idea how I could have gotten it.”

After suspicion rose that Nickels could have the rare infection, but before his diagnosis, his emergency department doctor, Matthew Shannon, M.D., admitted him to the hospital and alerted hospital epidemiologist and infectious disease doctor, Nicole Iovine, M.D., Ph.D.

Iovine sees the flow of events in Nickels’ case as a prime example of excellent interventionist medicine.

“When Dr. Medina realized that Adam needed to go to the emergency department, that was a life-saving intervention. Dr. Shannon realizing that he couldn’t go home, but he needed to be admitted: that was the second life-saving intervention. That’s huge,” Iovine said. “Then, when he got here, it was realized that he had this potentially life-threatening infection, meningococcemia, and he was treated appropriately and rapidly.”

Iovine was called in to ensure that no significant exposures of the bacterium to UF Health staff had occurred. She works on a team treating patients like Nickels who develop an infection that, left untreated, can spiral into a condition called sepsis.

Sepsis is the body’s extreme response to severe infection. It’s common, deadly and happens fast, as blood becomes overwhelmed by bacteria and organs shut down due to low blood pressure. Sepsis is the final stage of infection and is the number one cause of mortality in hospitals.

“Sepsis is the final common pathway by which many common infections can kill you,” Iovine said. “If someone has terrible pneumonia, for example, we may know that the infection is in the lungs, but the overwhelming response to that infection, which is sepsis, that’s how people die.”

Iovine works with a team to implement a set of procedures created to ensure a standardized approach for preventing sepsis. Through this, when patients come into the hospital, nurses observe them for signs of sepsis risk. If signs are evident, special nurses, called STAT nurses, are called in to perform a sepsis evaluation. If sepsis is still a possibility after a final physician evaluation, steps for sepsis prevention are activated.

Due to these protocols, Nickels was immediately administered broad-spectrum antibiotics and sepsis was prevented. Today, he is alive to tell his story of beating the odds and overcoming meningococcemia.

“His case was a beautiful example of when things work right,” Iovine said. “It was a great example of how everything works with protocol. Timing is key. Acting early saves lives, and I can tell you, without any reservation that if this had not been caught early, he would be dead.”

After leaving the hospital, Nickels had a midline intravenous catheter for continued antibiotic infusion. He was constantly winded and was unable to do anything active for about a month. Residual headaches from the illness forced him to slow down his studies, but Nickels managed to make enough progress that, miraculously, he never fell behind.

Nickels went on to graduate from UF in May of 2018. He is now back to his normal routine and is as active, if not more so, than he was before his illness. Due to the quick and effective work of UF Health physicians, Nickels has no permanent damage.

“I definitely use a lot more hand sanitizer,” Nickels said. “I could’ve died, lost a foot or arm, been partially blind or lost my hearing, but I was given this gift of being okay again. You have to appreciate that. You walk away with a profound sense of gratitude for everybody.”

In Iovine’s mind, while Nickels case ended positively, it’s impossible to leave a sepsis-prevention case and feel like you’re finished, especially when death by sepsis is still so common. For this reason, Iovine, other physicians, nurses and pharmacists meet in a sepsis committee three times a week to review every case of sepsis that occurs at UF Health.

“As part of that review of each case, we look at if we did everything correctly, if there are ways we can improve, and provide feedback to the caretakers to see how we can make it better and improve the process,” Iovine said.

Due to the dedication of the sepsis-prevention team, there has been a 26 percent decline in sepsis mortality at UF Health Shands Hospital since 2015, but Iovine is not satisfied.

“We can always do better when it comes to sepsis prevention,” she said. “So, we’re not going to be content, and we’re never going to sit back.”

UF is leading the way in sepsis research with The University of Florida Sepsis and Critical Illness Research Center, which studies long-term effects and outcomes in patients treated for sepsis in the surgical and trauma intensive care units at UF Health Shands Hospital. The first of its kind in the nation, the research center is dedicated to developing clinical solutions for sepsis and for conditions that develop after the infection.

September is Sepsis Awareness Month, and UF Health encourages patients, employees and the public to educate themselves about the signs and symptoms of sepsis.

About the author